What is philosophy to you?

I think of philosophy as something like reasoning in the pursuit of truth, but I don’t think that philosophy has the resources to determine what is true. What philosophy is very, very good at is uncovering alternatives. It shows us different ways that a given question might be answered, but it can’t, all on its own, tell us which if any of those answers is correct. I like to put it this way, “Philosophy is in the options business, not the truth business.” I might seem to be contradicting myself because I also described philosophy as reasoning in the pursuit of truth, but the key word here is “pursuit.” Philosophy needs the empirical disciplines (broadly construed) in order to contribute to that pursuit. So-called “pure” philosophy just spins its wheels.

How were you first introduced to philosophy?

My trajectory was nothing like normal. In fact, I was once affectionately described as a “feral philosopher.” Prior to doing my PhD in philosophy I had no background in philosophy at all. I dropped out of community college, and eventually did a master’s degree in psychoanalytic studies with Antioch University. I eventually approached Jim Hopkins at Kings College, University of London, about doing a PhD in philosophy, and despite the fact that I had no background in philosophy, Kings College took me on as a student. I was in my late 30s by then, with two young children and a full-time job. This was Britain, so I didn’t have to attend classes, just attend tutorials with Jim. To this day, I’ve never been a student in a philosophy class! Before transitioning to philosophy, I was a psychotherapist and psychotherapy trainer, so my PhD research focused on Freud’s philosophy of mind.

How do you practice philosophy today?

In my taxonomy, there are two kinds of philosophers: the puzzle-solvers and the artists. Puzzle-solvers do exactly what the term implies, in contrast, the artists paint pictures of the world that they think are worth taking seriously. Puzzle-solving is disciplined and analytical, but easily degenerates into triviality (I sometimes call it “high-class Sudoku”). Art-making is imaginative and creative, but easily degenerates into vague and sweeping claims, with little disciplined attempt at justification. I’m definitely closest to the picture-painting end of the spectrum, hopefully, tempered by an analytic intellectual conscience.

Why is philosophy important to you?

I know that it’s Quixotic, but I want to change the world, and the practice of philosophy is the best way for me to have some impact. For that reason, I concentrate on several issues that make a difference to the quality of life on Earth. For nearly twenty years now, I have focused on the phenomenon of dehumanization, which I define as the attitude of conceiving of others as less-than-human creatures. Because I want to change the world, it is very important to me to address non-philosophers. I’ve written three books on dehumanization, all of which are accessible to non-specialists. To be frank, the rarified and esoteric atmosphere of much of professional philosophy often strikes me as a scandalous squandering of intellectual capital that could be used more constructively. Philosophy is for the world, not just for academic philosophers.

What books, podcasts, or other media would you recommend to anyone interested in philosophy?

The answer to this question will depend on the philosophy-consumer’s particular interests. Because I work on dehumanization, race, genocide, and related matters I mainly read history and psychology rather than philosophy, so I might not be the best person to ask! In the straight-up philosophy literature, I greatly admire David Lewis’ On the Plurality of Worlds. For sheer clarity and intellectual humility, Lewis is hard to beat, even though his basic thesis is wacky. There are some terrific books by historians addressing the interface between ethics and fascism. I particularly recommend Claudia Koontz’ The Nazi Conscience and Johann Chapoutot’s The Law of Blood: Thinking and Acting Like a Nazi. Finally, two exciting, empirically-grounded books by philosophers are Tommy Curry’s The Man-Not: Race, Class, Genre, and the Dilemmas of Black Manhood and Ditte Munch-Jurisic’s Perpetrator Disgust: The Moral Limits of Gut Feelings.

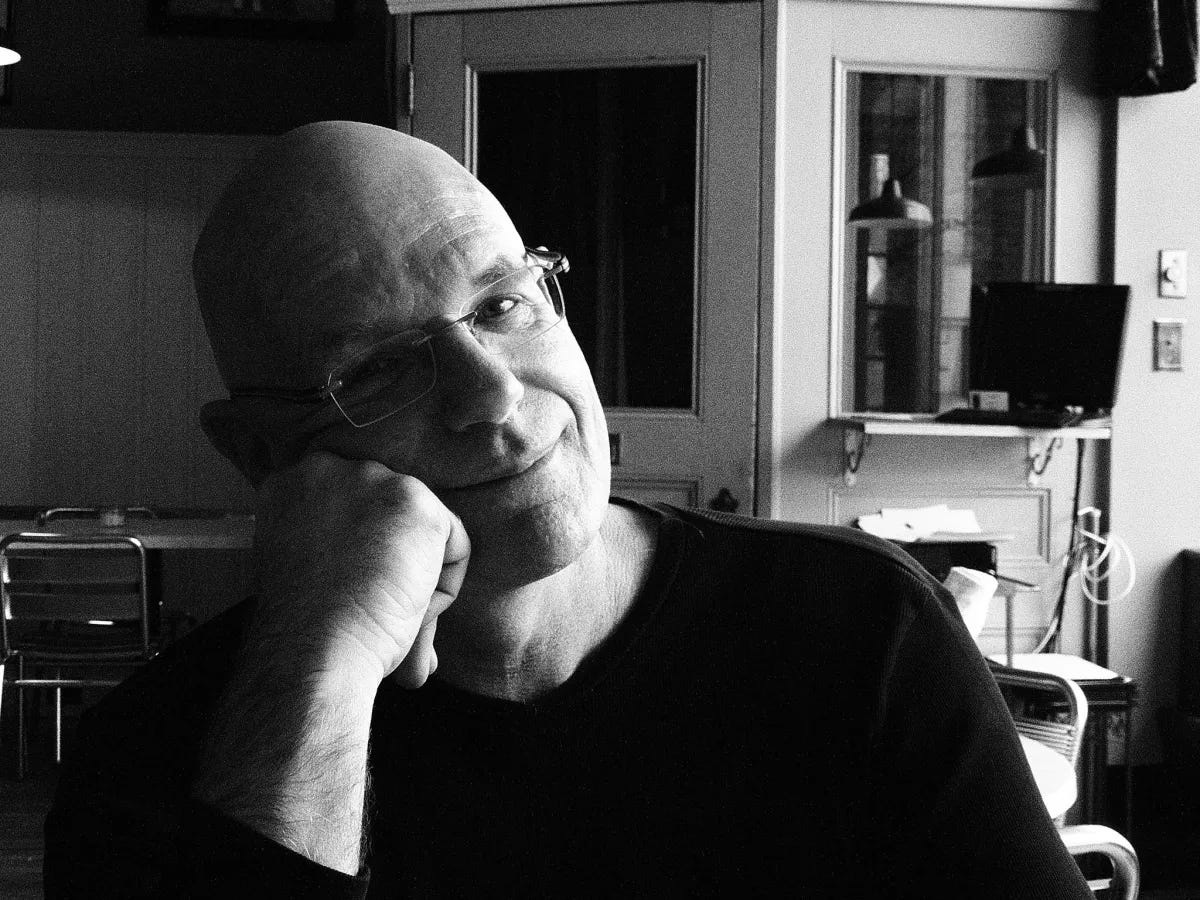

David Livingstone Smith is professor of philosophy at the University of New England. He is the author of ten books, including Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave and Exterminate Others (St. Martins Press, 2011) was awarded the 2012 Anisfield-Wolf award for nonfiction, and his most recent book Making Monsters: The Uncanny Power of Dehumanization (Harvard, 2021) has been shortlisted for the Nayef Al-Rodhan International Book Prize in Transdisciplinary Philosophy.